See my updated post Git Low Effort Workflow (GLEW for short).

This blog post is a response to a reddit user but reddit limited me to a 10,000 character response. As a compromise I decided to say everything I wanted to say and link back from this reddit thread. The following is a quote of myself and this blog post is an elaboration on my reply.

Except what you deployed to prod wasn’t technically the thing that was tested with that workflow (workflow problem and not tool problem)

(i.e. even the same SHA256 hash artifact). Expanding on this. I recommend that your final release pipeline be from a Git tag.

A simple example is a Java library. Your library is released to a hosting provider like Sonatype Nexus. By releasing from a tag you publish the binary only once and ship that binary through different environments of the testing process (dev, qa, stage, prod). It is important to note that what lands in production is what was tested. I recommend the full testing process be performed on the Git tag (even duplicating the fast running tests run on a pull request).

The same statement should apply to any “artifact” even if that “artifact” is a Docker image or a whole machine (like an AMI in Amazon AWS if you practice immutable infrastructure).

I’d like to explain the workflow I’ve developed to help relay exactly what I mean by this.

- Before you read on

- Git workflow in a picture

- CI pipelines in a picture

- What makes this different?

- Real world example

- Summary

Before you read on

While some of the diagrams I’ll share show Jenkins. I’d like you to focus on

the workflow itself since it is tool agnostic and is generally a decent workflow

I developed to be in a CI as code system where CI code is stored in the repo of

the code being built (like Travis CI, CircleCI, Jervis: Jenkins as a service,

Jenkins multibranch pipelines, Jenkins X, etc

Git workflow in a picture

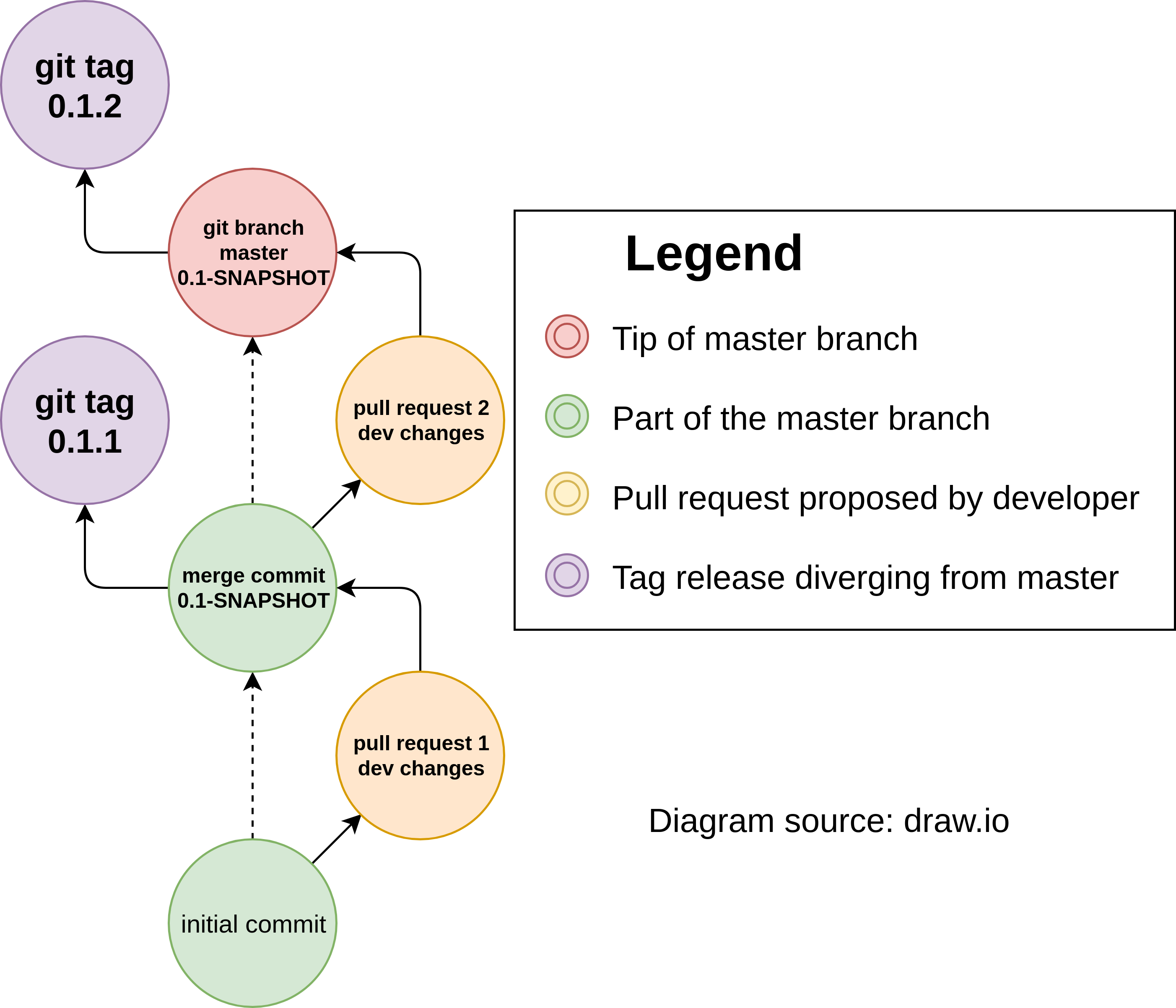

It’s easy to forget (or overlook) that tags, like branches, are just references to commits. A tag can diverge from a branch just like a branch can diverge from a branch. With that in mind here’s a diagram showing a flow.

Generically, I call my method GitHub flow with releases. I’ll explain later

why I think this is different.

The thing I’d like to point out in the above diagram is that there are three separate events.

- Developer opens a pull request (or merge request) and adds commits to it. This is one pipeline.

- A pull request is merged which triggers another event in a CI system. On the branch, there’s a script which should automatically bump the version (but not push to master). The bumped version diverges from master and pushes the tag back to the SCM host.

- When a tag is pushed another event is triggered for the pipeline.

CI pipelines in a picture

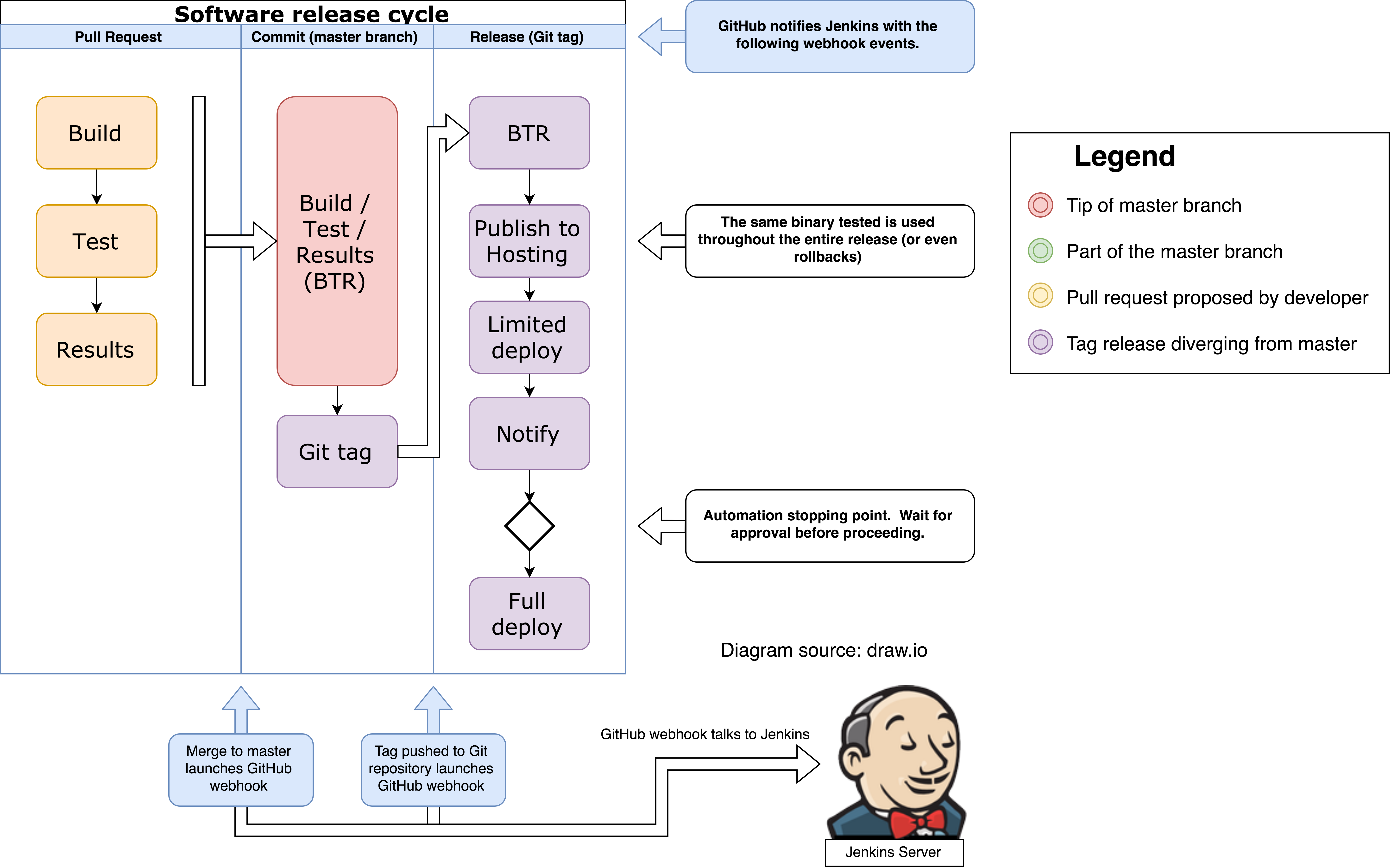

Here’s a second diagram I created. It is color coordinated similar to the “GitHub flow with releases” diagram. The following diagram illustrates a different dimension of the three events.

- The first vertical column is viewed from top to bottom and illustrates a testing pipeline on a pull request.

- The middle column is a pipeline read from top to bottom for when a branch is

pushed (in this case

master). The branch pipeline also auto-version bumps and pushes the tag back (but does not push the version bump back to master) - The third column is a pipeline read from top to bottom and illustrates a production release pipeline.

Note: Each column in the following diagram is a bubble in the

GitHub flow with releasesdiagram.

What makes this different?

What do I mean by, “I developed it”? Most interpretations I’ve read about tag releases involve pushing back to the master branch or tagging directly from the master branch. Throughout my career implementing workflows in mega-sized companies I’ve found many limitations to this. Automated releases can be really hard. Often, some of the tips I mentioned (such as Git tags diverging from branches) are things I came to realize by myself and have not ever seen it mentioned in actual articles which discuss Git in the context of automated releases or team workflows.

I also want to explain why I feel it’s different than similar “tag release” methods.

- First, there’s no race condition between an automated release process pushing

back to the

masterbranch and developers trying to merge changes. Every merge implies a release and every release diverges from master instead of pushing back to it. This means multiple releases can happen in parallel and do not conflict with each other. Developers can release practically as fast as they can merge code. - Hotfixes work well with the same diagram. In my original diagram, let’s say

0.1.1is in production and needs to be hotfixed but0.1.2is the latest development release. I would cut a short-lived0.1.1-hotfixbranch which then has similar release automation asmasterbut instead releases hotfix releases like0.1.1.1,0.1.1.2, etc for each merge into the short lived hotfix branch. It is up to the developers to ensure that their hotfixes to the0.1.1series of releases make it back intomasterfor general development and ensure the bug is not re-introduced in the future through automated tests. - This is a sane single-branch workflow which encourages many small releases (every PR merged is a tag release cut). However, due to thorough testing not every release will necessarily reach production. This is basically GitHub flow except that every merge commit initiates a tagged commit diverging from it. Every tagged commit is a version bump based on other commits released.

Real world example

If you’ve read this far I imagine you’re interested to learn more. I’ve created a real world example project which is a Jervis CI project (a side project of mine where I support Travis CI YAML in Jenkins but not relevant for this discussion). I’ll explain the parts that matter.

GitHub project example

samrocketman/demo-jenkins-world-2018-groovy-jar.

The CI as code files are in .jervis.yml and the .ci/ folder. The

.jervis.yml file eventually launches the

.ci/Jenkinsfile.

Inside of the Jenkinsfile you’ll see two sections of code:

Create a Tag(happens only on the master branch; not pull requests and not tags)Release to GitHub(only happens on a tag)

This is a really simple example so the “Tag release” phase does’t have much because it’s not a real product.

But this is basically where all of the production pipeline would occur.

- Run fast unit tests (runs from PR)

- Run longer running integration tests against non-shared services (may or may not be done in a PR but definitely in a tag pipeline)

- Deploy to dev (deploy to dev can also happen from pull requests but should also happen in the production tag release pipeline)

- Deploy to QA. There might be a manual approval gate or if you’re confident in your automated QA then proceed normally.

- Deploy to stage. Run automated smoke tests on stage. The smoke tests runs some real world API calls on the service to make sure it is working correctly.

- Production roll-out (which varies depending on your architecture). Personally, I like twitter murder but I’ve not ever seen it run anywhere than twitter. Now a days a production rollout is some form of lazy rollout with automatic rollback. This is typically handled by another tool designed for it such as Netflix Spinnaker.

There’s a lot of things I purposefully left out above because I could talk all day about this and I feel like I’ve written too much already.

Summary

The important thing to note here (to re-iterate my first sentence) is you really want to deploy the things you actually tested (binary-wise). Your prod pipeline should be running everything your test pipelines ran and then some if you want it to be fully automated.

Let’s remember the real problem being solved. Increase your confidence to deliver your product on a regular basis. This workflow enables that and by keeping changes small you reduce the risk of change.