- Background

- Git Low Effort Workflow

- Additional reading

If you want to skip the background and read about my new workflow, then jump down to Git Low Effort Workflow (GLEW for short).

A summary of this post: I highlighting ways traditional workflows break down in practice. I then propose a solution I adopt in practice when developing large scale delivery infrastructure (think thousands and tens of thousands of developers trying deliver software to production daily).

Background

Why another workflow?

Why yet another workflow? In my career I have tried and practiced many workflows: Git flow, GitHub flow, GitLab flow, and some flavor of these workflows which try to work in automated releases in their own way. All of them seem to gloss over automated managing of version numbers.

All of these workflows fall down one of these areas:

- Overcomplexity

- Challenge for automated releases (automated version bumping)

- Compliance (don’t deploy to prod from pull requests)

Overcomplexity

One could argue that knowing Git is part of a developer’s job since it’s a tool of their trade. However, to apply this blanket statement to “all developers” is not only potentially descriminatory… it’s also not realistic to expect all people to be the same level technically at any particular thing.

For example, in my experience Git flow does a good job at change control but seems to struggle with automated version bumping of software and its complex workflow tends to put a lot of effort onto the developer to understand how to manage Git. I’ve seen places that try to automate Git flow and the end result is only a few people who really understand Git get what is going on and can problem solve, the rest are left in the dark and tend to create a support burden because they need to fix a conflict resolution or some other thing which is supposed to happen automatically, doesn’t.

How not to automatically release new versions

Automatically managing version numbers and new releases with bumped numbers can be hard but not impossible.

Automated releases tend to be where all of these workflows get into trouble, especially in highly parallelized systems interactions like between GitHub and CI/CD tools. For instance, very active projects where developers accidentally outrace the automated system pushing a version bumped commit.

Another scenario is where developers try to manage version numbers in pull requests but then run into trouble trying to revert. If you’re managing a version number in a pull request, then you’ve already complicated your ability of simply clicking that revert button in the GitHub UI to rollback code without rolling back the version number.

Since all workflows I mentioned don’t cover how to automatically manage version numbers, it is left up to the implementor or developer to figure it out. Some fall back to just baking the Git hash into their software releases because managing version numbers has no immediately obvious solution that scales well.

Compliance

I’ve worked for and with companies that have strict 3rd party auditing requirements in how they manage and roll out software to customers. Every workflow seems to have some trouble one way or another.

You can practice Git flow but if your development is on one branch and your releases on a completely different branch then you’re either rolling out untested code to production or you testing the same thing multiple times. The nuance I’m getting at is ideally, in practice I’ve found testing with the same artifact (SHA256 hashed consistently to be clear) throughout all of your environments to deliver to production is the most reliable. If you’re rebuilding your software or artifact or docker container before pushing to a promoted environment, then you’re introducing significant variance.

Many of these compliance bodies tend to demand some form of:

- Prove there’s a process of change management to production (sometimes manually gated)

- Prove the process was followed.

- Prove who was involved (approvals, development, reviews, etc.)

You can and should protect branches and tags, but you can’t deploy to production unreviewed from a pull request. Most of this is all process around tooling and workflow and not necessarily a flaw in the workflow itself. It’s just that some workflows make this a lot harder than others. i.e. don’t deploy to prod from a pull request. Preview environments are cool and okay. Preview environments are all that should be done in a pull request when you factor in strict regulatory bodies and compliance bodies.

Git Low Effort Workflow

This workflow is low effort because:

- It supports continuous automated release and version bumping as part of its design.

- Developers can roll back code just as easily as introducing it (click the revert button).

- Releasing and quality control is centered around doing everything from Git tags as opposed to specific branches or pull requests. Branches are not precious or to be released from, only tags.

- This takes the benefits from easy to use workflows like GitHub flow where developers can work off of a branch and only work about pull requesting (or merge requesting) back to a central shared branch where releasing starts occurs.

- Merging to master branch doesn’t affect how automated releases occur. Many developers can merge to master concurrently and there’s no possibility for merge conflicts with an automated system publishing version bumped releases.

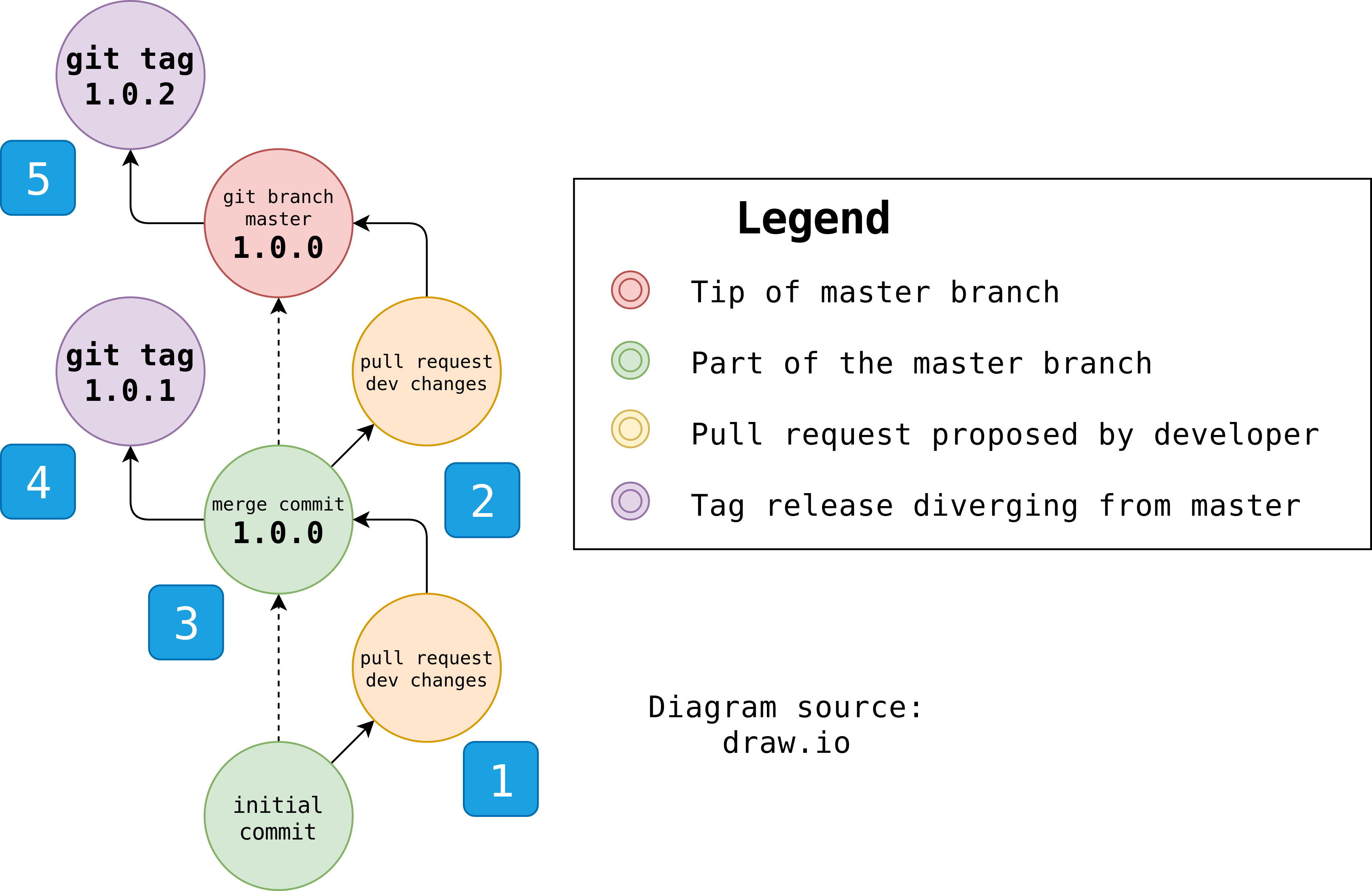

Figure 1. Diagram of GLEW with automated releases

The following diagram and description show how a developer contributes to the

master branch via pull requests. An automated system bumps the version and

releases a version bumped tag.

Figure 1. Automated release flow for Git Low Effort Workflow explained in 5 steps.

Developer opens pull request from feature branch

Developer opens pull request from feature branch

A developer opens a pull request with their code changes. The pull request should only contain code changes for their minor feature and not change any version numbers.

Feature branches can be created from repositories:

git fetch origin

git checkout origin/master -b myfeature

# make some changes and commit

git push origin -u myfeature

Or created from forks:

git fetch upstream

git checkout upstream/master -b myfeature

# make some changes and commit

git push origin -u myfeature

Automated checks pass and peer review occurs

Automated checks pass and peer review occurs

An automated system builds and runs tests. Peers review code and give their thumbs up to approve the change to be merged.

Automated version bumping upon merge to master

Automated version bumping upon merge to master

Pro tip: Git tags can diverge from branches just like branches can diverge from other branches.

The master branch contains some form of “latest” version such as

1.0-SNAPSHOT or in the case of Figure 1, the last 0 from 1.0.0 is treated

as a number to be incremented.

After a change is merged to master, an automated system runs to evaluate

existing Git tags and the version in the current master branch. This is used to

determine the next version bump release.

The automated system writes the version bump to source files and commits but

does not push the changes back to master. Instead, it tags the commit with

the version number and pushes the tag. This tag becomes a release which

diverges from master.

The automated system sees that master branch contains version 1.0.0 so it

searches for all tags which match 1.0.[0-9]+. It takes the highest numbered

tag and increments by 1. In this case, because no releases have occurred,

yet, version bump and Git tag 1.0.1 is released.

Release and deployment flow occurs from Git tag

Release and deployment flow occurs from Git tag

GitHub fires webhooks when branches and tags are pushed. An automated system

should receive a webhook when 1.0.1 tag is pushed to the repository. It

should start the release flow. This release flow from Git tag can do several

things such as:

- Release the artifact to a binary repository.

- Promote the released artifact through different environments (dev, stage, prod).

Second automatic release from version bump

Second automatic release from version bump

Let’s say a developer goes through the same process again (pull request, review,

merge, etc.). The next time a merge to master occurs the automated system

will evaluate all Git tags based on the version in master which is 1.0.0.

It searches all Git tags which match 1.0.[0-9]+ and bumps the highest found

version. In the diagram, since 1.0.1 has already been released then the

automation bumps to 1.0.2.

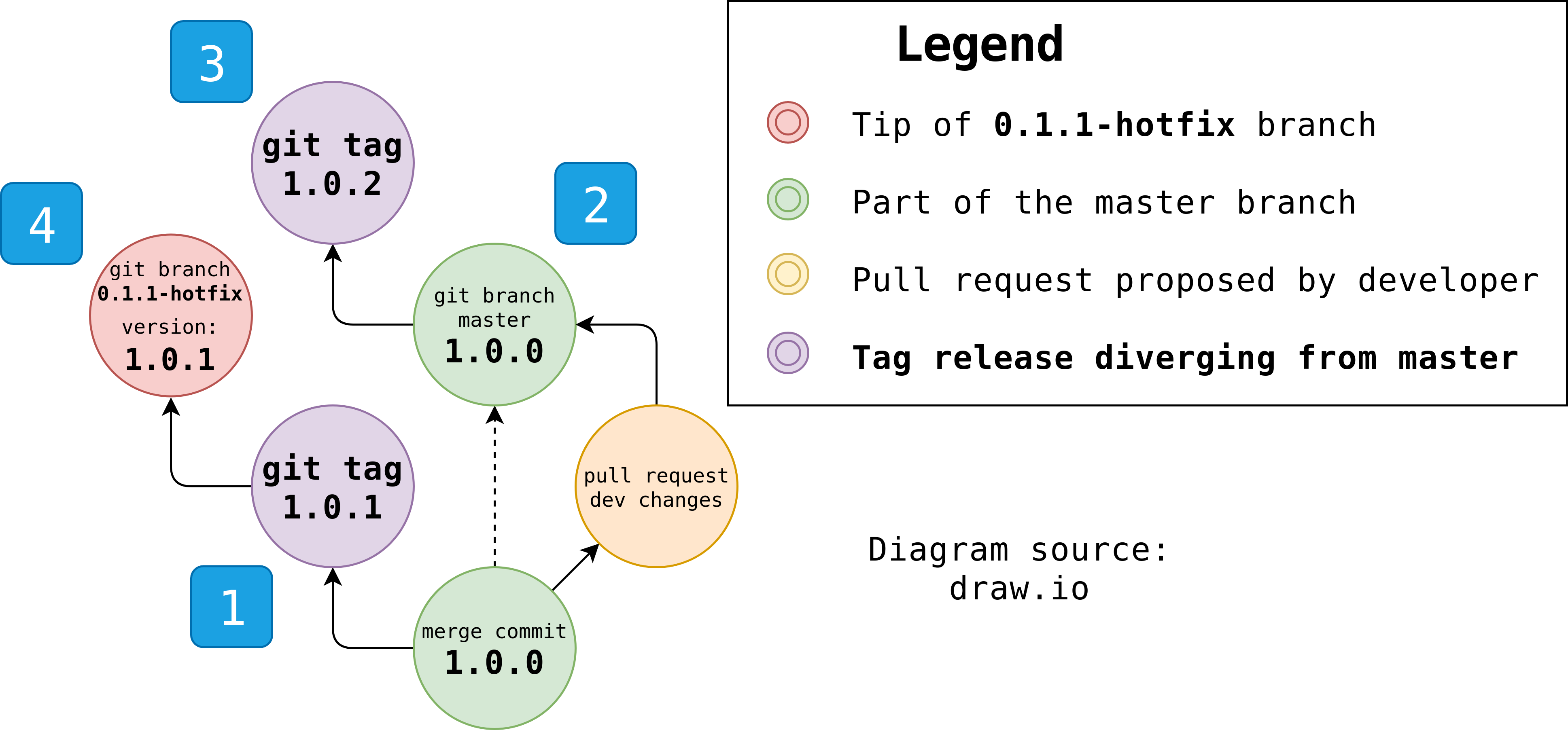

Figure 2. How to release hotfixes with GLEW

Scenario: Let’s say version 1.0.1 is currently running in production. An

issue has been discovered in 1.0.1 and absolutely must be fixed (hotfixed

even). However, unstable development has released version 1.0.2. This means

you must create a release from the prior stable 1.0.1 without including

changes from unstable 1.0.2.

Figure 2. Create a hotfix branch from a prior stable release.

Git tag 1.0.1 is deployed but needs a hotfix

Git tag 1.0.1 is deployed but needs a hotfix

1.0.1 is currently deployed to production. A critical issue is discovered and

must be fixed immediately.

A developer has released an unstable feature

A developer has released an unstable feature

Let’s face it, sometimes all the checks can pass and everything looks good until you realize a change is critically broken and can’t reach production.

A merge to master releases unstable 1.0.2

A merge to master releases unstable 1.0.2

The automated version bumping system releases 1.0.2 from master.

1.0.2 can’t go out because a critically blocking problem was discovered with

the release in staging right before it was about to roll out to production.

Fortunately, it didn’t break production because it wasn’t promoted.

However, 1.0.1 must be hotfixed immediately to meet a customer SLA.

Create a hotfix branch from release 1.0.1

Create a hotfix branch from release 1.0.1

Pro tip: Git branches can be created not only from other branches, but also created from Git tags. You should enable branch protection on hotfix branches.

Create a hotfix branch which will serve as the branch for automatically releasing hotfixes.

git fetch origin --tags

git checkout 1.0.1 -b 1.0.1-hotfix

git push origin 1.0.1-hotfix

Now, you create feature branches off of the hotfix branch. Hotfixes, should be

pull requested into the 1.0.1-hotfix branch.

git checkout origin/1.0.1-hotfix -b my-feature-fix

# make your changes and commit

git push origin -u my-feature-fix

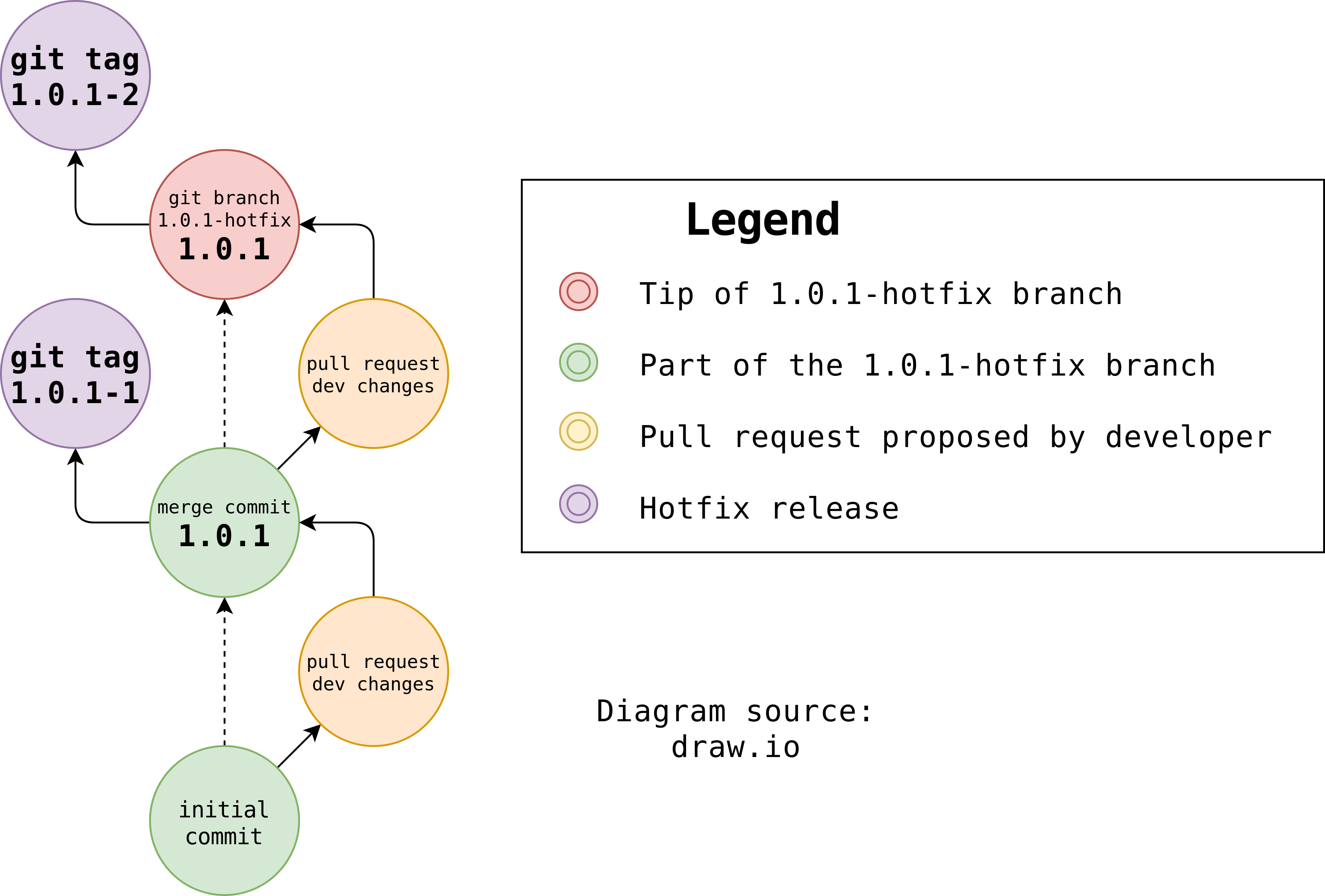

The hotfix release flow becomes the exact same flow as for master branch.

See diagram of GLEW hotfix workflow which looks the same as master (click to expand)

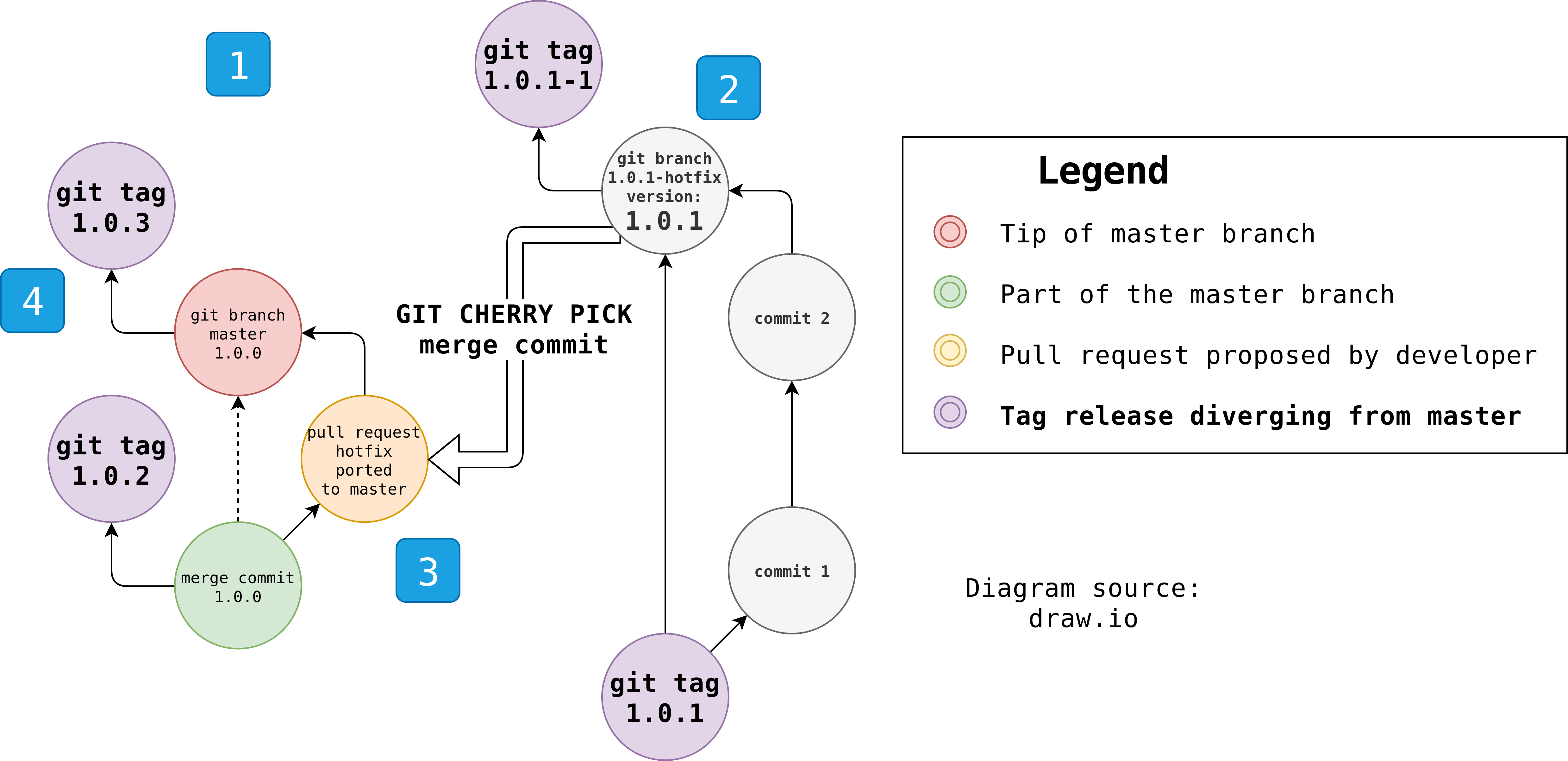

Figure 3. Port hotfixes back to master branch

Pro tip: Cherry picking merge commits gets the combined diff of all commits from a pull request.

So you’ve released your hotfixed 1.0.1-1 and 1.0.1-2. Production is now

stable and it’s time to port all hotfixes back to the master branch. This can

be done by cherry picking the merge commits.

Figure 3. Port hotfixes back to master branch by cherry-picking merge commits from hotfix releases.

Diagram overview

Diagram overview

To the left of the diagram is the master branch where there’s the 1.0.2

release (if you recall earlier we needed to hotfix 1.0.1).

To the right of the diagram is the 1.0.1-hotfix release flow. Let’s say a

developer released two hotfix releases:

1.0.1-1(hyphen 1 at the end).1.0.1-1is shown in the diagram.1.0.1-2(hyphen 2 at the end).1.0.1-2is not shown in the diagram.

These releases are consistently formatted with semantic versioning.

How to reference merge commits

How to reference merge commits

In the Git Low Effort Workflow, Git tag releases are commits which are one ahead

of a merge commit or tag which is diverging from the developed branch (e.g.

master or 1.0.1-hotfix).

We want to migrate hotfix releases 1.0.1-1 and 1.0.1-2 back to master

branch. You can reference their respective merge commits the following way.

1.0.1-1~1

1.0.1-2~1

Pro tip:

~1(ends with tilde one or~1) in the above references refer to Git ancestry references.1.0.1-1~1is short hand for one commit before1.0.1-1. One commit before1.0.1-1is the merge commit.

Create a branch from master and cherry pick merge commits

Create a branch from master and cherry pick merge commits

Pro tip: Cherry picking only picks from the literal commit. So it will not include version bumping in the cherry-picked diff.

You’ll need to fetch the origin branches and tags in order for this to work.

git fetch origin

git fetch origin --tags

git checkout origin/master -b my_fixes

Cherry pick each hotfix release separately. They’ll show up as two separate commits.

git cherry-pick -m 1 1.0.1-1~1

git cherry-pick -m 1 1.0.1-2~1

Note that each Git tag ends with ~1 (tilde one) in order to reference the

ancester merge commit from the Figure 3 diagram.

Push your changes up to your feature branch.

git push origin -u my_fixes

Review and merge.

Merging ported hotfixes creates a normal release 1.0.3

Merging ported hotfixes creates a normal release 1.0.3

The latest release is 1.0.2. When you merge all of your ported hotfixes, they

will be bumped into the next release 1.0.3. All development on from the

master branch after 1.0.3 release will include the necessary hotfixes.

Additional reading

- See also Scalable Delivery Workflow which focuses a little more on how to deliver but doesn’t cover automated releases as well as this post.

- Refer to Jervis 1.6 API for Jenkins. It contains a couple tables illustrating version numbers, Git tags, and what the next release should be. It’s a decent example at implementing automatic releases in Jenkins.